In our previous article, we introduced the idea that investors often misstep — not because of poor information, but because of deeply ingrained behavioural biases. Those patterns aren’t random. They’re systematic. And they’re surprisingly predictable.

This follow-up takes a deeper dive. We explore not just what behavioural biases are, but why they exist, how they impact financial decisions, and what advisers can do to navigate them. This article is for those who already understand the basics and want to better integrate behavioural finance into both planning conversations and portfolio design.

The message is simple: cognitive bias is not a flaw of some investors — it’s a fundamental part of being human. And for advisers, success often lies not in overcoming it, but in working with it.

1. The Science of Decision-Making

Behavioural finance draws heavily from the work of psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who famously proposed the dual-system theory of thinking:

• System 1 is fast, intuitive, emotional, and automatic.

• System 2 is slow, effortful, rational, and reflective.

While we like to believe System 2 governs our financial decisions, most day-to-day choices —especially under pressure — default to System 1. It’s efficient, but not always accurate.

That’s where heuristics come in: mental shortcuts that allow us to make decisions quickly, using patterns and context rather than complete analysis. Heuristics are evolutionarily useful —for identifying threats or making time-sensitive calls — but they often lead to cognitive biases in complex environments like investing.

The result is what economist Herbert Simon called bounded rationality: people make the best decision they can, given their limited time, information, and processing capacity.

2. Four Foundational Bias Clusters

Biases tend to cluster around themes — emotional responses, information filtering, social influence, and cognitive framing. Below we unpack four core groups, their scientific basis, and the financial impact they tend to produce.

Loss, Fear, and Avoidance

Key Biases:

• Loss Aversion: People feel the pain of a loss about twice as strongly as the pleasure of an equivalent gain.

• Hyperbolic Discounting: Preference for immediate rewards over larger, future gains.

• Status Quo Bias: Resistance to change, even when better alternatives are available.

Neuroscience Insight:

Losses activate the brain’s amygdala, the fear centre responsible for fight-or-flight responses. This makes financial loss not just undesirable, but emotionally painful.

Adviser Implication:

Clients may flee from volatility, abandon long-term plans during downturns, or avoid actionaltogether.

Confidence and Mental Shortcuts

Key Biases:

• Overconfidence Bias: Overestimation of one’s own skill, control, or predictive ability.

• Confirmation Bias: Tendency to seek information that supports existing beliefs.

• Self-attribution Bias: Taking credit for wins while externalising blame for losses.

Behavioural Basis:

These biases arise from dopaminergic reinforcement — we get a psychological “reward” from being proven right. This can harden narratives and discourage critical thinking.

Adviser Implication:

Clients may disregard diversification, ignore contrary evidence, or believe they can outsmart markets.

Social and Herding Impulses

Key Biases:

• Herding: Imitating others’ actions, especially under uncertainty.

• Social Proof: Assuming a decision is correct because others are doing it.

• Availability Bias: Judging probability based on memorable or recent events.

Behavioural Basis:

Humans are social learners. During periods of uncertainty, the brain leans on group behavior to reduce ambiguity — even if the crowd is wrong.

Adviser Implication:

Clients may chase returns, rotate into popular themes late, or panic sell en masse duringcorrections.

Mental Anchors and Framing Effects

Key Biases:

• Anchoring: Fixating on irrelevant reference points (e.g., past prices).

• Framing: Reacting differently depending on how a decision is presented.

• Mental Accounting: Treating different “pots” of money inconsistently.

Cognitive Basis:

These biases stem from our need for cognitive efficiency. Anchors simplify complex decisions. Frames reduce ambiguity. Mental accounts create perceived structure.

Adviser Implication:

Clients may become paralysed by past highs, misallocate based on “fund labels,” or make inconsistent budgeting choices.

3. Case Studies: When Bias Becomes Behaviour

Example 1: The Overconfident Market Timer

An experienced investor becomes convinced the market is overdue for a correction and moves all assets to cash, citing “instinct” and “signals.” The portfolio misses a sustained rally, and the client re-enters near the top — compounding poor outcomes.

Underlying Biases: Overconfidence, confirmation bias, availability bias

Adviser Action: Rather than confronting the client directly, the adviser uses structured decision rules and scenario modelling to encourage gradual re-entry aligned to goals, not predictions.

Example 2: Anchored in the Past

A retiree refuses to sell a long-held shareholding because it’s “still below what I paid for it.” Despite poor fundamentals and multiple advisories, the anchor holds.

Underlying Biases: Anchoring, status quo bias

Adviser Action: Shifts focus from purchase price to opportunity cost, illustrating potential gains from reallocation and linking them to future lifestyle goals rather than technical arguments.

4. Behavioural Tools in Practice

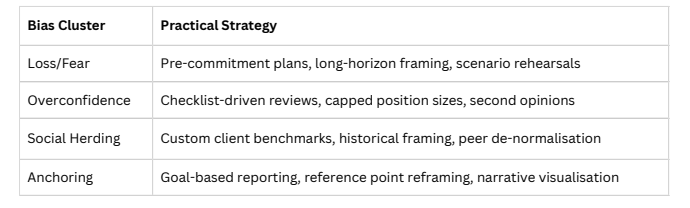

To counter these biases, advisers need more than technical skill — they need process, structure, and client alignment. Below is a summary of practical strategies mapped to each bias cluster.

These tools do more than correct behaviour — they prevent poor decisions before they occur.

Cognitive bias is not a glitch — it’s a feature of the human operating system. Investors are not spreadsheets. They are people. And successful advisers recognise that portfolios need to be designed for behaviour, not just for return.

The best behavioural finance strategies aren’t lectures — they’re systems. They build clarity, reduce friction, and guide clients through volatility with fewer emotional missteps.

At Innova, we believe in designing portfolios and planning frameworks that are not just academically sound, but emotionally robust. Because it’s not enough to be right. You also need to help clients stay invested long enough for being right to matter.

To receive 0.25 Technical Competence CPD points for this article, complete the quiz here.

References

• Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin Books.

• Simon, H. A. (1955). “A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99–118.

• Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). “Advances in Prospect Theory.” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

• Shiv, B., et al. (2005). “Investment Behavior and the Negative Side of Emotion.” Psychological Science, 16(6), 435–439.

• Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2001).“Boys Will Be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 261–292.

• Bikhchandani, S., et al. (1992).“A Theory of Fads, Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change asInformational Cascades.” Journal of Political Economy, 100(5), 992–1026.

• Thaler, R. H. (1999).“Mental Accounting Matters.” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making,12(3), 183–206.

Important Information

This document has been prepared by Innova Asset Management Pty Ltd, ABN 99 141597 104, which is a Corporate Authorised Representative of Innova Investment Management, AFSL 509578.

The information contained in this document is commentary only. It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice. The views expressed are subject to change at any time based on market and other conditions. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Before making any investment decision you need to consider your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances.