It’s easy to believe that investors fail because of poor information or bad timing. But more often, the real culprit is behaviour. Not just investor behaviour, but human behaviour — our brains, wired for survival, often work against us in financial decision-making.

Behavioural finance sits at the intersection of psychology and investing, explaining why people systematically deviate from rational choices, even when logic, data, and advice are all pointing in the right direction. For advisers, understanding these patterns isn’t academic — it’s essential.

In this article, we’ll explore:

• The key behavioural biases that drive poor decisions

• Why they occur

• Real-world examples of how they play out with clients

• Practical techniques for navigating them.

Because when advisers understand behaviour, they can help clients stay on track — and stay invested — through uncertainty, noise, and emotional volatility.

The Human Brain Is Not Built for Finance

The average brain processes around 11 million bits of information per second, but our conscious mind can handle only about 50 bits at a time. That’s roughly equivalent to a 1930s teletype machine. It’s fast enough for basic survival decisions — like noticing a predator or avoiding a hot stove — but ill-suited to the complexity of long-term investing.

Faced with overwhelming data, our brains conserve energy by relying on shortcuts: fast, intuitive judgments known as heuristics. These are often helpful — we don’t need to analyse every threat or calculate the physics of every ball we catch — but in investing, they can lead to consistent, costly errors.

This is the foundation of behavioural bias: systematic deviations from rational thinking that feel right in the moment, but lead to poor outcomes over time.

Five Biases That Derail Good Plans

Let’s unpack five of the most common behavioural biases affecting financial decisions — and why they matter so much for advisers.

Loss Aversion

People feel the pain of losses about twice as strongly as the pleasure of gains. This “pain gap” can make investors overly conservative, quick to sell winners, and reluctant to hold onto assets through normal drawdowns — even when those moves are well within expected volatility.

Confirmation Bias

When someone has a belief, they tend to seek out information that supports it — and ignore evidence that contradicts it. In investing, this leads clients to cling to narratives, favour familiar assets, and resist advice that challenges their mental model of what “should” happen.

Overconfidence Bias

Clients often overestimate their knowledge, forecasting ability, or timing skill. This can manifest as concentrated bets, refusal to diversify, or misplaced certainty in predictions — behaviours that tend to underperform over time.

Herding Behaviour

People are social. When uncertainty rises, they tend to follow others — even into speculative bubbles or panic-driven selloffs. Herding behaviour can feel safer, but often leads to buying high, selling low, and copying poor decisions made by the crowd.

Anchoring Bias

Clients often fixate on irrelevant benchmarks — a past share price, a peak portfolio value, or the purchase price of a property. These anchors can distort future decisions, especially when the reference point is no longer meaningful in the current context.

Real-World Case Examples

While biases are well-documented, practical illustrations of how they emerge — and how advisers can manage them — are less common. Below are two anonymised examples drawn from real-world behavioural patterns.

Case Study 1: The Panic Seller

Bias: Loss Aversion + Recency Bias

Example Client: A cautious, long-term investor with a diversified portfolio calls their adviser during a steep market drop. They’re anxious, checking their account daily, and feel emotionally overwhelmed. They say: “I just can’t watch it fall anymore — I want out.

Although the portfolio remains aligned to their long-term strategy, the recent losses loom large. The client forgets previous gains and focuses solely on the current pain.

Adviser Interventions:

• Pre-commitment framing: The adviser reminds the client of their agreed strategy and reaffirms what decisions were made during calm periods — not in reaction to volatility.

• Reframing with context: Using a simple visual of past drawdowns and recoveries, the adviser helps the client understand this isn’t abnormal — it’s expected.

• Time horizon reset: By anchoring back to the client’s original goals (retirement income, not next-quarter returns), the adviser shifts focus from now to what matters.

Outcome: The client stays invested. Six months later, markets recover, and the portfolio rebounds — reinforcing both trust and discipline.

Case Study 2: Chasing the Crowd

Bias: Overconfidence + Herding

Example Client: A new investor, energised by a wave of news about electric vehicle (EV) stocks, wants to overweight their portfolio toward one “breakthrough” company. Friends and media commentary reinforce the belief that this is a sure thing.

The client shows high conviction and dismisses valuation concerns or diversification advice.

They’re confident they’ve found the next big winner.

Adviser Interventions:

• Diversification guardrails: The adviser implements a rule that no single stock can exceed a set percentage of the portfolio, protecting against overexposure.

• Decision checklist: Before executing the trade, the adviser walks the client through a behavioural checklist — including questions like, “What would need to happen for you to sell this stock?”

• Scenario planning: The adviser presents downside scenarios to test emotional resilience: “If this stock fell 30% in three weeks, what would you do?”

Outcome: The client adjusts their allocation, adds exposure via a thematic ETF, and avoids over-concentration. When the stock later underperforms, the client is disappointed — but not devastated. They remain engaged, confident in the process, and focused on long-term goals.

From Theory to Practice

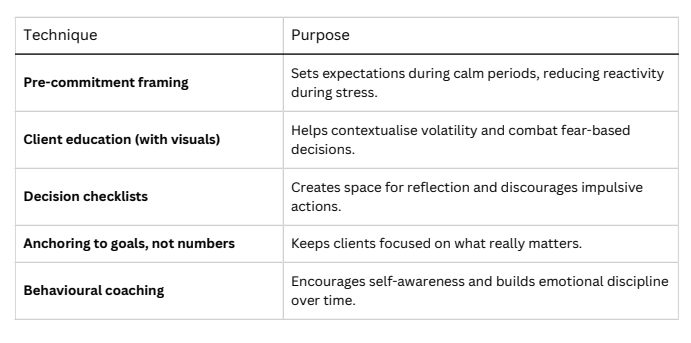

Understanding behavioural bias is just the beginning. Here’s how advisers can apply this knowledge to build stronger, more resilient relationships:

The most successful advisers today are not just portfolio constructors — they’re behavioural coaches. They understand that returns matter, but staying invested matters more.

Behavioural finance isn’t about fixing flawed people — it’s about acknowledging how all of us, clients and professionals alike, are influenced by emotion, stress, and noise. By identifying biases, naming them, and designing processes to neutralise them, advisers can help clients avoid costly detours and stay the course.

In the next article, we’ll explore how compartmentalised investing — using tools like mental accounting and asset–liability matching — can turn cognitive quirks into planning strengths. Until then, remember: the plan is only as good as the behaviour that supports it.

To receive 0.25 Technical Competence CPD points for this article, complete the quiz here.

Important Information

This document has been prepared by Innova Asset Management Pty Ltd, ABN 99 141 597 104, which is a Corporate Authorised Representative of Innova Investment Management, AFSL 509578.

The information contained in this document is commentary only. It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice. The views expressed are subject to change at any time based on market and other conditions. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Before making any investment decision you need to consider your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances.