This is part II of the series Behind the Behaviours: Using Revealed Preferences to Understand What Clients Can’t Tell You.

When it comes to couples and relationships, what goes unsaid is often more important than what gets said.

It’s no different in an advice context. It’s critical for advisers to unearth what often goes unsaid, especially in cases where one partner doesn’t feel confident or able to articulate their preferences.

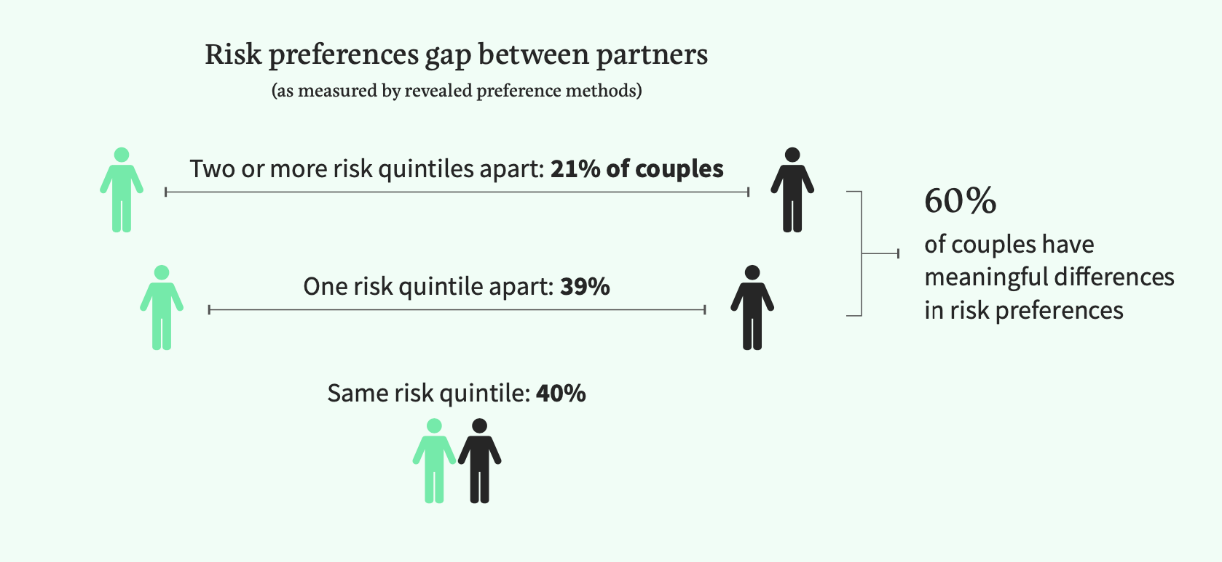

This really matters. In the domain of investment risk, for example, 60% of couples under 60 years old have meaningful differences in their risk preferences.1 When that kind of gap exists, it creates a serious AUM flight risk for advisers (more on that below). Not to mention the potential for complaints and disputes down the track.

Revealed preference tools are central to helping advisers detect these preference differences. As a reminder (and as discussed in Part I), revealed preference methods combine standard and behavioural economics with decision science and gamified experiences. They let us precisely measure preferences through a client’s decisions, so we can detect hidden wrinkles in their preferences that clients couldn’t express themselves, and that no questionnaire could pick up.

As we’ll see, how advisers conduct risk profiling sets the tone for advice relationships with couples in subtle but very important ways.

Shachar Kariv, Professor and former chair of the economics department at University of California at Berkeley and Chief Scientist of Capital Preferences, explains the problem of differing preferences in couples.

The not-so-odd couple: Anna and Angus

To unpack this more, let’s go inside the risk profiling experience with a couple – Anna and Angus – who are just beginning a relationship with their adviser. While Angus and Anna have a similar risk tolerance, Anna has higher loss aversion than Angus, though she would have a hard time articulating it [see Part I on Loss Aversion]. Anna and Angus don’t realize it, but they have a meaningful difference in their risk preferences.

Their adviser jointly administers a risk tolerance questionnaire (RTQ) to them. Incidentally, this is the most common approach for risk profiling couples, occurring over half the time.2

Angus is the “household CFO” (statistically the most common scenario in male – female couples), and grabs the pen to start filling out the RTQ. Anna defers to Angus, maybe weighing in here or there, but much is left unexpressed and unheard as Angus completes the RTQ.

“In almost every couple, there is a financial spouse and a non-financial spouse, and too often, the non-financial spouse becomes wallpaper in meetings.”

– Tim Maurer, Head of Wealth Management, Triad Financial Advisers

To be sure, Angus’ and Anna’s adviser has positive intent to get a joint answer that reflects both their risk preferences. In reality, a jointly administered RTQ creates a situation where the non-financial partner’s preferences aren’t truly expressed and accounted for.

Recall, because 60% of couples have meaningful differences in risk preferences, this really does matter – it’s a key driver of both partners feeling heard and understood, and having confidence in the portfolio recommendation and advice that follows. And it’s a key input for advisers to make suitable recommendations at the household level.

Here’s the kicker – when there is a meaningful difference in risk preferences that goes unaddressed, it’s an assets under management (AUM) risk for the adviser. Couples like Anna and Angus are six times as likely to decrease AUM, and only half as likely to bring held away assets to their adviser in the coming year.3

The acid test question: Do both partners truly feel heard and accounted for?

Zooming out, the risk profiling experience for Anna and Angus is often the start of a subtle, unwitting, and harmful pattern in adviser relationships with couples. Anna, the non-financial spouse , doesn’t feel fully heard. When a relationship starts that way, it often continues that way on autopilot—inertia takes over.

Eye-tracking studies show that 60% of advisers’ focal time is on the male partner in live meetings with heterosexual couples.4 36% of female partners think their adviser makes more eye contact with their partner.5

To be clear, this is often unwitting and unintended on both the part of the adviser and the household CFO.

Nonetheless, it has real effects on client confidence and satisfaction. Non-financial partners who don’t feel heard have a much lower Net Promoter Score – 20-30% vs. 80-90% for those who feel heard and equitably treated.6

Moreover, where it can really bite is years later with a retired couple who has built up a large AUM nest egg. Female partners who don’t feel heard are only 17% likely to stay with their adviser if their partner exits the picture, vs. 60-70% likely to stay if they feel heard.7

So, 20 years down the line, should Angus pass away early, Anna is very likely to take their advice relationship – and now much larger nest egg – elsewhere. She never really felt heard by or connected to her adviser.

What can advisers do about it?

Getting after this unwitting inequitable treatment is a blend of adviser self-awareness, plus communication and facilitation competencies with couples. We provide some references at the end of this article that speak to these “people” factors. But wise advisers will also make systematic changes to their advice process.

On this latter point, a “first principles” place for advisers to start is changing how they risk profile couples. Why?

• Risk profiling happens early in the relationship – it sets the tone early and can begin the relationship on the right foot, where both partners feel fully heard right out of the gate.

• There are meaningful, hidden gaps – with 60% of couples having meaningful differences in risk preferences, it really is a chance to measure each partner’s preferences so they both feel heard.

• Individuals’ risk preferences evolve over time, so it creates a natural occasion to re-engage both partners annually.

Best practices

Here are five best practices for risk profiling couples, considering the problems highlighted in this article.

1. Risk profile each partner independently – get a “pure” read on each partner’s risk preferences, free from the “social” bias of the other partner (and even the adviser).

2. Use a revealed preferences risk profiling method to detect hidden differences – oftentimes, the reason there are meaningful risk preference differences between partners is because one partner has much higher loss aversion than the other (see Part I in the series). RTQs can’t measure loss aversion; revealed preference methods can.

3. Give each partner a chance to unpack their preferences with you – have a guided, thoughtful discussion with the couple, stepping through the results for each partner. Discuss and explore similarities and differences in the scores, so both parties feel heard and accounted for.

4. Have a defensible method for combining preferences – this will help you ensure the household CFO’s preferences aren’t the default, and lets you show how portfolio selection best represents both partners’ preferences, as revealed in their individual risk profiles. Revealed preferences, because it has mathematics “under the hood”, best enables this combination and optimization.

5. For easy re-measurement, use a risk profiling method that is intuitive and quick – so you can establish an annual routine of measuring each partner’s preferences, independently. Think of yourself as a physician running an annual blood test for each partner “patient” – it’ll create the occasion for a meaningful check-in, in which you can make each partner feel heard and well-tended to, and in which you can detect and address important preference changes.

Professor Kariv explains how revealed preferences enables aggregation of couples’ risk preferences.

Toward All Clients’ Voices Being Heard and Accounted For

That’s how revealed preferences can help detect hidden risk gaps between partners and address the AUM flight and retention danger that comes with a non-financial partner who doesn’t feel heard.

In Part III, we’ll take a look at how hard it is for clients to self-report their changing preferences over time, and what advisers can do to stay ahead of that.

You can access more information on how revealed preferences can be used within your business and with clients here.

Resources & References – Upskilling advisers’ communication and facilitation skills with couples

We relied heavily on Capital Preferences’ research for this article. The full research study is available here – Not-So-Odd Couples: Creating an Equitable Advice Experience for Modern Couples.

There’s a growing set of studies and literature that can help advisers when it comes to equitably engaging couples. The focal point for upskilling is communications and facilitation skills in couples scenarios, with special emphasis on:

• Asking open ended Qs, to better get at “whys” and motivations

• Not taking sides (wittingly or unwittingly)

• Not bringing one’s own biases into engaging the partners (individually or together)

• Managing non-verbal communications, such as eye contact and hand gestures

• Using case studies and practicing in front of peers

• Case study discussions

• Role-plays

• Video advisors in simulated or real interactions with couples (family and friends), followed by self-critique and peer/expert feedback

Further Reading:

- Overcoming the Unique Communication Challenges of Advising Couples, Kitces.com

- Client Relationships and Family Dynamics: Competencies and Services Necessary for Truly Integrated Wealth Management, Journal of Wealth Management, April 2010. Psychologist James Grubman and Professor of Organizational Systems Dennis Jaffe outline a competency framework

- 2021 Women and Investing Study, Fidelity

- Seeing the Unseen: The Role Gender Plays in Wealth Management, Merrill Lynch, 2022

1. Not-So-Odd Couples: Creating an Equitable Advice Experience for Modern Couples, Capital Preferences, 2023, p. 13.

2. Ibid, p. 15.

3. Ibid, p. 14.

4. Seeing the Unseen: The Role Gender Plays in Wealth Management, Merrill Lynch, 2022.

5. Not-So-Odd Couples: Creating an Equitable Advice Experience for Modern Couples, Capital Preferences, 2023, p. 9.6.

6. Ibid, p. 10.

7. Ibid, p. 10.